Pensioner tells of struggle to survive as air strikes devastate energy infrastructure across Ukraine.

Liudmyla Oleshko has not left her freezing apartment in Kyiv for two months, resorting to using six jumpers and a battery pack to warm up as Russian air strikes leave her without electricity and water for days on end.

The 75-year-old spends her days shuffling around, swaddled in several layers and three pairs of socks as temperatures outside plunge to as low as -20C.

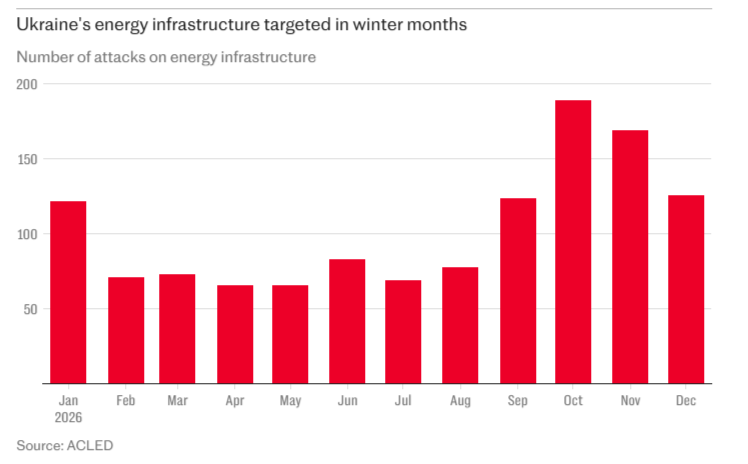

In the past two months, Russia has ratcheted up its strikes on Ukraine’s energy grid, cutting off power and heating to much of the country during a bitterly cold winter.

Liudmyla, who lives alone on the 12th floor of her block, has not been able to tackle the flights of stairs since the attacks cut power to the lift and plunged the stairwell into darkness.

It is the second time war has rendered her life in Ukraine unbearable. She was forced to flee her home in Mariupol in February 2022 before a months-long Russian bombardment of the city eventually led to its occupation.

She is one of millions living in Kyiv and beyond without access to light, heating and water after Russia repeatedly hammered the energy grid in an effort to force Ukrainians into submission.

Yet, in her frost-bitten home, Liudmyla remains defiant: “We are Ukrainians. We are strong people. That’s all.”

The unusually cold winter and the toll of nearly four years of war have made the impact of Vladimir Putin’s attacks that much worse this time.

On Thursday, Donald Trump declared with fanfare that Putin had agreed to a one-week cessation of its long-range strikes on Ukraine’s energy grid, saying it was “very nice” of the Russian president to acquiesce to the request.

But relief in Ukraine was short-lived after Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman, said the pause would only last until Sunday, just as temperatures are set to plummet once again as low as -22C.

Putin is hoping that plunging the Ukrainian capital into unbearable cold will crush morale, forcing Ukraine to surrender its land, resources and people.

But Ukrainians like Liudmyla are refusing to be deterred, and resorting to unusual methods to stay warm.

Some are using heating bricks on gas stoves as improvised radiators and pitching tents in their own homes to trap warmth.

Liudmyla told The Telegraph that in the few hours she gets electricity each day, she becomes a hive of industry, washing her hair, cleaning the apartment and frying as much food as she can before the power turns off again.

This month, following a Russian attack, she was left with no electricity or water for three days. “As I felt the frost strike, I sat down and I made 120 varenyky dumplings. Then at least I’m doing something.”

She keeps her food warm all day by putting it on top of a battery. And she keeps fresh food brought to her by her granddaughter in containers balanced on her balcony.

Sometimes other unorthodox solutions present themselves. When she wakes up freezing, she dances to warm up.

“When I get too cold, I just drink a glass of vodka or cognac,” she says as she laughs. When her flat flooded with icy water from an upstairs flat, she rubbed her hands and feet with vodka to stop herself from getting sick from the cold.

Liudmyla is not always in such a buoyant mood. She sometimes calls her granddaughter Khrystyna in tears, talking about how she wishes she could return home to Mariupol and see the sea again. But what remains of her city, now under Russian occupation, will be unrecognisable.

For those with young children, the struggle to keep going can become unbearable.

One such resident is Iryna Makarchuk, a 33-year-old mother to 13-month-old Marko who lives in the affluent commuter city of Vyshneve, two kilometres south of Kyiv.

Ms Makarchuk told The Telegraph that with only intermittent electricity and water in short supply, she has been bathing her young son using bottled drinking water, and bought a generator on credit so she could keep refrigerated food cool and turn the lights on at night.

Living high up in an apartment block, she has to carry Marko in her arms up nine flights of stairs in the pitch black, sometimes donning a head torch.

After an attack in mid-January, she only had one hour of electricity every day for a week – one hour a day to cook, bathe Marko and herself, charge all of her devices and consider the laundry.

“I had to stay in a good mood because of my child,” Ms Makarchuk said as she fed Marko hot chicken and rice cooked on top of a gas cylinder. “But as a mother, it’s difficult for me.”

She lamented that the lack of electricity means it is hard to cook fresh, nutritious meals for her son.

“You scroll on Instagram and see these meals for babies, toddlers, with fresh fruits and vegetables. And you think, wow – and he’s eating something from a restaurant, or leftovers from yesterday,” she said.

At least, with their new thick, insulated windows, the overnight attacks are less likely to jolt them awake in the small hours, though they still have to hide in the bath or basement when Russia fires missiles and drones towards the city.

‘The Russians want to destroy us as people’

And when it comes to the one-week ceasefire agreed by Putin, Ms Makarchuk says she has little faith – “because it’s Russia.”

“They have never done what they promised, what they told us. It’s going to be -22 degrees at night. And the Russians, they want to kill us, they want to destroy us as people. Not even as a country, but as people,” she said.

“We saw it every year. You think, how can this get worse. And then every year, it gets worse.”

Liudmyla’s granddaughter Khrystyna also says nobody in Kyiv believes that the ceasefire will last. “We’re all preparing for another attack in the next few days.”

Khrystyna, who delivers food and warm clothing to Liudmyla while caring for her young child, said it was heartbreaking to see her grandmother stranded in her freezing apartment.

“It’s unfair,” she told The Telegraph while putting a shawl around her grandmother’s shoulders. “She doesn’t have a place to go back to, because her house [in Mariupol] was bombed by Russia… people like that, they have this big trauma already, and now they have to be reborn again because of this crisis in Kyiv.”

In response to the crisis, the Ukrainian capital has opened 1,300 so-called “invincibility points” – heated tents, rail carriages and public buildings where residents can charge devices and receive hot food – while curfews have been relaxed to allow travel to the refuge points during the freezing nights.

Yet many elderly and infirm residents, like Liudmyla, remain effectively marooned in high-rise buildings without lifts or heating, unable to reach shelter.

At one heated tent in the Voskresenka neighbourhood, nestled between a cluster of blacked-out apartment blocks more than 20 storeys high, The Telegraph saw volunteers serving hot tea and ladling out servings of bohrach, a hearty meat stew with root vegetables.

Children sat at long tables with crayons and games, still wearing bobble hats and layers of jumpers underneath puffer coats, while queues of elderly and parents piled in, their shoes squeaking on the canvas floor awash with icy black sludge.

“It’s the coldest winter I’ve ever known. Mostly we have just two, three hours of power. We wear the same clothes inside that we wear outside and we come here for hot food,” said 27-year-old Tetiana as she left the tent with her five-year-old son Andriy to trudge home down a road without street lighting.

“We thought about leaving Kyiv, but there’s nowhere to go. It feels like we will stay here until we freeze to death.”

On Friday, Volodymyr Zelensky cast new bitter recriminations at Europe for what he saw as a failure to safeguard Ukraine’s shattered energy infrastructure with adequate air defence provisions, as huge attacks on January 9, 20 and 24 left extensive damage across the grid.

“Imagine this: I know that ballistic missiles are incoming against our energy infrastructure, I know that Patriot systems are deployed, and I know that there will be no electricity, because there are no missiles to intercept them,” the Ukrainian president said.

Energy repair workers have become local heroes for their rapid round-the-clock work, but Denys Shmyhal, the energy minister, said on Jan 27 that 710,000 people remained without electricity.

A spokesman for DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy company, told The Telegraph that its operators were forced to restore 277 substations, transformer and distribution points and 2,426 power lines with a length of more than 8,000 kilometres in 2025 after they were damaged by Russian missile and drone attacks.

Several of the workers have died throughout the war in the process of restoring the strained, precious grid.

And the week-long ceasefire is only a small reprieve during the sub-zero conditions.

Kaja Kallas, the EU’s top diplomat, told reporters on Thursday that Ukraine was facing a “humanitarian catastrophe”.

“It’s a very hard winter and Ukrainians are really suffering. There is a humanitarian catastrophe coming there,” she said at a meeting in Brussels.

As the city awaits the resumption of bombardment, Kyiv’s residents know they are facing more grinding months ahead with no way out, only forward.

“I wish I could just go home,” Liudmyla told The Telegraph, gazing out of the window at the dark, towering clusters of apartment blocks all around. “I want to see the sea.”