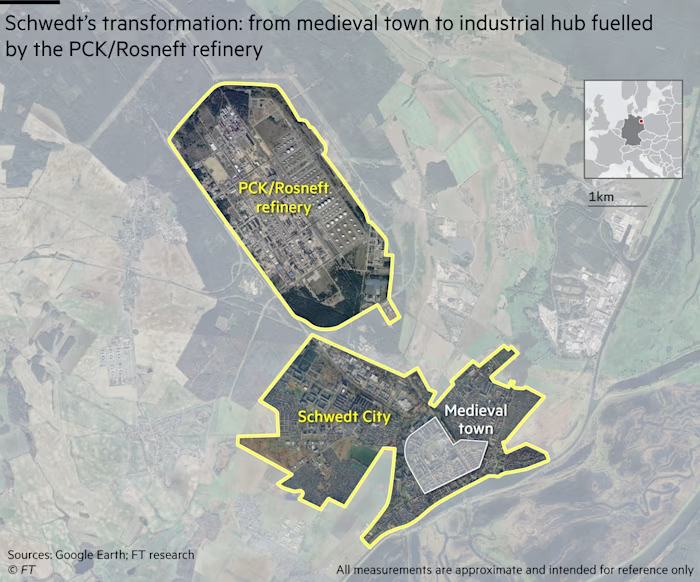

In a sprawl of concrete 100km north of Berlin, a Soviet-era refinery has become a hostage to Europe’s tangled geopolitics: Russia owns it, Germany runs it and US sanctions could soon shut it down — risking a fuel chokehold on the German capital.

Such is the precarious state of the Rosneft-owned PCK oil-processing plant in Schwedt — which supplies 90 per cent of the petrol, kerosene and heating fuel to Berlin, its airport and the surrounding state of Brandenburg.

With an April 29 deadline looming, when an American sanctions exemption expires, the government is in talks with the US administration to secure another reprieve. But early-stage work has also resumed on nationalisation as a measure of last resort, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

“The signs from the US are positive [about extending the exemption] but you never know with this administration,” said one of the people. “So expropriation is being looked at again.”

Time is of the essence: Tankers must be booked one to two months in advance, while both suppliers and customers are seeking reassurances now that the refinery will honour its contracts.

Successive governments have so far avoided expropriation for fear of Russian retaliation. But the cabinet of Chancellor Friedrich Merz may be faced with no other choice.

A shutdown would mean “thousands of trucks that would need to shuttle from Bavaria and from across the country” to supply Berlin around the clock, said another person familiar with the matter.

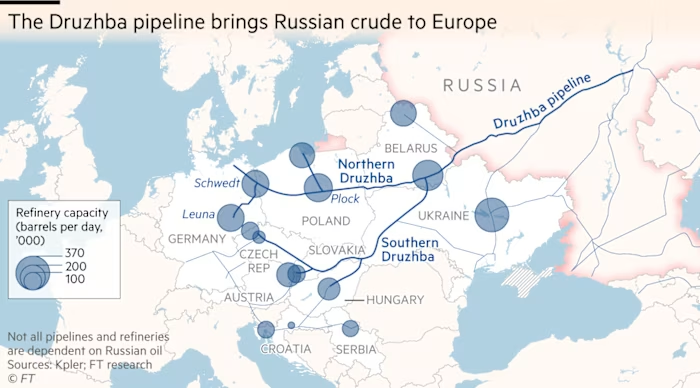

The fate of a refinery sitting on the Druzhba (Friendship) oil pipeline underscores how, nearly four years into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Germany is still grappling with decades of reliance on Russian energy.

It also shows how the unpredictability of US President Donald Trump’s administration has forced a rethink in Berlin, where the government is now weighing measures once considered too radical.

In 2022, after Europe, the US and other allies imposed a price cap on Russian oil, the German government assumed control of PCK’s operations by placing it under trusteeship. But it did not seize the shares, which remain 54 per cent owned by Rosneft, partly because it feared Moscow would retaliate by nationalising German businesses in Russia, including retailer Metro, officials said.

Berlin has since rushed to seek alternatives to the Siberian crude that flowed for six decades through Russia’s 4,000km pipeline to Schwedt.

But in October, amid US-Russia talks on ending the war in Ukraine, Washington imposed sanctions on Rosneft and its assets in Europe, bringing the refinery to the brink of bankruptcy.

The US move was not co-ordinated with Berlin. Banks halted the refinery’s transactions and stopped processing salaries. The German government eventually secured a six-month reprieve from US authorities, arguing that the Russian oil group had no effective control of the plant.

Schwedt, population 33,000, enjoyed a postwar revival when the refinery was built in the 1960s, in what was then the Soviet-aligned German Democratic Republic.

“Every bus, every police car, every rescue service, every plane — all are running on PCK fuel,” said Annekathrin Hoppe, the town’s Social Democrat mayor. “This company must be able to continue to operate.”

If the refinery were forced to halt operations, some 3,000 trucks would need to shuttle continuously to avoid supply disruptions, said Konstanze Fischer, an ophthalmologist and founder of Zukunft Schwedt (Future Schwedt), a group of residents supporting the plant. “We’re a melting pot of problems,” she said.

Built as a symbol of the close relationship between East Germany and Moscow, the PCK plant continued to prosper after the collapse of the Soviet Union and German reunification.

The 2022 decision to place the refinery under the supervision of the country’s federal energy regulator was met with disbelief.

The pipeline was part of a “long tradition of friendship with Russia — the meaning of ‘druzhba’ in Russian”, said Michael Kellner, a Green MP who as junior minister was involved in the decision. “People were very proud of it.”

Reinhard Simon, a regional MP from the leftwing, Moscow-friendly Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), called the move to stop using Russian oil “irresponsible” and driven in part by the “demonisation of fossil fuels”.

“We have the feeling here that we are collateral damage,” Simon said.

Danny Ruthenberg, head of the refinery’s work council, added: “If you turn off the tap, then you should have turned on another one beforehand.”

Stabilising the refinery was difficult because it was integrated into Rosneft’s supply chain designed to process Urals crude. Supplies came at low cost and allowed PCK to pay 45 days after delivery, according to a person with knowledge of the operations.

Kazakhstan’s state oil company, KazMunayGas, which is now the main supplier, sells crude at a higher cost and demands advance payment, the person said. PCK was also forced to look for supplies from Polish and German ports, at greater expense, and to adapt its operations to different types of crude.

After dropping sharply, utilisation had recently been brought back above 85 per cent of capacity, Ruthenberg said.

The government is now planning to replace the current trusteeship, which needs to be renewed by the Bundestag every six months, with a more permanent legal arrangement by linking it to the EU sanctions regime. The move is designed to convince US authorities to grant another reprieve, short of expropriating Rosneft.

A spokesperson for the economy and energy ministry said expropriation was “not under discussion”. The ministry was in contact with US sanctions authorities “regarding approval beyond April 29”.

The plant’s unusual stewardship has scuppered large investments, such as a €400mn plan to upgrade a pipeline linking Schwedt to the port of Rostock or a project to produce green hydrogen.

“It’s simply not lucrative enough,” Ruthenberg said.

Rosneft did not immediately reply to a request for comment. The company previously said it was seeking to sell its stake. Qatar’s Investment Authority expressed interest in 2024 but withdrew after failing to agree on a price, according to people familiar with the talks.

Shell, another investor, which holds a 37.5 per cent stake in PCK, has also struggled to find buyers for its shares. Refinery insiders said KazMunayGas had also been sounded out to buy it.

“The best solution would be an oil company, with the knowhow and the money to steer the refinery into the future. But the global refinery players are all withdrawing from Germany,” Ruthenberg said, citing low margins and the increasing share of EVs.

As a result, the refinery is slowly decaying and burning through cash reserves. “You may have one more year to attempt a major transformation. After that things could get gloomy,” an insider said. The most likely outcome was a government bailout, they added.

Expropriation would carry risks. Rosneft may dispute the level of financial compensation and challenge the decision in court. Moscow could also disrupt supplies of Kazakh crude transiting the Druzhba pipeline.

But Kellner, the former junior energy minister, said nationalisation would allow the German government to organise a sale, particularly if a peace deal were reached in Ukraine.

“My concern is that a US investor takes over,” he said, “and that the profit is shared between the US owners and the Russian suppliers, and the bill is paid by German car drivers.”

Yet, in Schwedt, residents are still hoping that Russian oil will flow again one day.

“We sincerely hope, for Ukraine but also a little selfishly for ourselves, that a peace deal is reached,” said Fischer from Future Schwedt. “When peace returns to a reasonable level, we will have to trade with Russia again.”