After the stand-off over Greenland, European leaders are having to consider what would happen if Washington leaves the military alliance.

Since its founding nearly eight decades ago, Nato, the world’s mightiest military alliance, has rested on a confidence trick — an assumption that every member, and above all its pre-eminent one, the US, would defend an ally under attack.

That confidence had already been severely dented by Donald Trump’s repeated questioning of Nato’s usefulness and disavowal of America’s mutual defence obligations. This month it was shattered by Trump’s threats to seize Greenland from Denmark, a close Nato partner.

It is a seismic change that will force America’s bereft allies reluctantly to reimagine how they organise their own security.

“This crisis is much worse than anything we’ve seen in 77 years of Nato history and in many ways, anything since December 7 1941, which is when the United States formalised the idea that the security of Europe was fundamental to the security of the US,” says Ivo Daalder, a former US ambassador to Nato. “That idea that was formalised in treaty form in 1949 is gone. It’s over.”

European leaders, while relieved that Trump had stepped back from his threats against Denmark and its European partners, will find it hard to forget what would have been a fatal blow to an organisation that has kept them safe for generations and has helped underpin a rules-based global order.

“Now we have a crisis. It’s obvious,” said Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk at an EU summit in Brussels last week.

Rachel Ellehuus, head of the Royal United Service Institute in London and a former Nato and Pentagon official, says: “The damage has been done, and uncertainty about the credibility of the US commitment is now an undercurrent of transatlantic relations.” She adds: “[Trump] is too mercurial and the resistance from inside the US too inconsistent.”

While this remains a highly sensitive subject for most Nato members, some European officials have begun to press for a more active debate about the security architecture for the continent.

“We need to have a clear strategy of how we are replacing, from a material point of view, all those [US] capabilities, what they call material defence readiness,” Andrius Kubilius, the EU’s defence commissioner, tells the FT.

“But also we shall need to discuss more and more . . . our understanding about our institutional defence readiness. What we can call the European pillar of Nato. Those discussions also should become more and more intensive. It’s the proper time now. That is what we need to do.”

Before Trump’s latest Greenland threats, European powers were only beginning to grapple with the implications of a Trump administration shifting the burden of the continent’s security away from America. Having mostly underinvested in their own defence for decades, they hoped that a pledge by all members of the alliance last year to spend 5 per cent of GDP by 2035 on defence and security would buy them some time to re-arm and substitute some of the critical military assets they have relied on America to provide.

US secretary of war Pete Hegseth last year called on European allies to take “primary responsibility for Europe’s conventional deterrence and defence”. The US national defence strategy published on Friday described the Russian threat to Nato’s eastern flank as “manageable”. The Pentagon, it said, would “calibrate US force posture and activities in the European theatre to better account for the Russian threat to American interests as well as our allies’ own capabilities”.

Pentagon officials told European diplomats they wanted this to happen by 2027, according to a report by Reuters last month. That would be a much more accelerated timeline for European militaries that would leave gaping holes in their defences, but it would still be something of a transition.

However, Trump’s apparent openness to invading an ally has changed the game.

Even the most robust supporters of America’s role among European defence officials say they can no longer afford to be complacent about US intentions.

Last week it emerged that Canada’s armed forces have even conducted scenario planning for a possible US invasion, however unlikely.

America’s Nato allies have been jolted from fear of US abandonment to fear of US hostility, says Steven Everts, director of the EU Institute for Strategic Studies in Paris.

“Now it seems we are in quite a different debate: do we trust the US guarantee at all? This is a much more difficult question because it is compelling people to think the unthinkable, that this is not about changing the security bargain between the US and Europe. This is about Europe essentially finding itself alone with a partially hostile America.”

European capitals have very different stances on just how much, and how fast, they should crawl out from under the US security blanket.

At a summit of EU leaders last Thursday to discuss the transatlantic relations, the 27 agreed on a “systematic reduction of dependencies from the US in the medium and long term”, according to an EU official briefed on the private discussion, but were split on the right approach to Trump’s remaining three years: engagement or estrangement.

Britain faces a particularly tough dilemma, given its close military and intelligence ties with Washington and its dependence on the US for maintaining its nuclear deterrent.

Rethinking security arrangements in Europe remains largely a taboo in official circles for fear of provoking Trump to walk away from Nato altogether or encouraging Russian President Vladimir Putin to exploit perceived weakness.

“We are in the process of creating a stronger Nato than we have ever seen since the end of the cold war,” Finland’s President Alexander Stubb tried to argue in Davos last week just as Trump took a wrecking ball to the alliance.

Even French President Emmanuel Macron, who famously declared the alliance “brain dead” in 2019, is careful not to question the alliance’s importance for Europe’s defence.

Yet if the US were to disengage from or abandon European defence would raise daunting challenges for European governments.

“If anyone thinks here . . . that the European Union or Europe as a whole can defend itself without the US, keep on dreaming,” Nato secretary-general Mark Rutte told the European parliament on Monday.

“If you really want to go it alone, forget that you can ever get there with 5 per cent [defence spending]. It will be 10 per cent. You have to build up your own nuclear capability. That costs billions and billions of euros.”

Rutte was also acerbic about the discussions on the so-called European pillar inside Nato. “A European pillar is a bit of an empty word,” he said. “I wish you luck if you want to do it . . . I think Putin will love it.”

Keeping the US involved in Ukraine has been a top priority for European leaders since Trump’s return to power a year ago, even at the cost of absorbing punitive US tariffs on EU goods last summer without retaliating.

If the US abandoned Kyiv it would be a heavy blow to Ukraine’s exhausted military and European officials say it would only encourage Putin to pursue his maximalist goal of Ukraine’s submission.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy showed little confidence in Europe’s ability to step up in a scathing speech last week in Davos: “Europe loves to discuss the future but avoids taking action today,” he said.

However, the effects of US abandonment would not be as critical as they seemed a year ago when the Trump administration briefly paused intelligence sharing and weapons deliveries. Other allies have stepped in with their own assets, say Ukrainian and European officials. Macron claimed this month that France now provided Ukraine with two-thirds of its intelligence. According to a western official, reliance on US intelligence for Ukraine could be largely reduced within months.

Although Ukraine still badly needs weapons from US stockpiles, especially for air defence, the shift to drone warfare and the rapid expansion of Ukraine’s domestic arms production, now accounting for 60 per cent of its needs, has lessened its dependency.

Even on air defence there are alternatives: Ukraine is due to receive the first of several new Franco-Italian SAMP/T NG long-range systems this year which France claims are more advanced than the Patriot, although they are not yet combat tested.

If supporting Ukraine without America is hard enough, defending Europe alone is next to impossible.

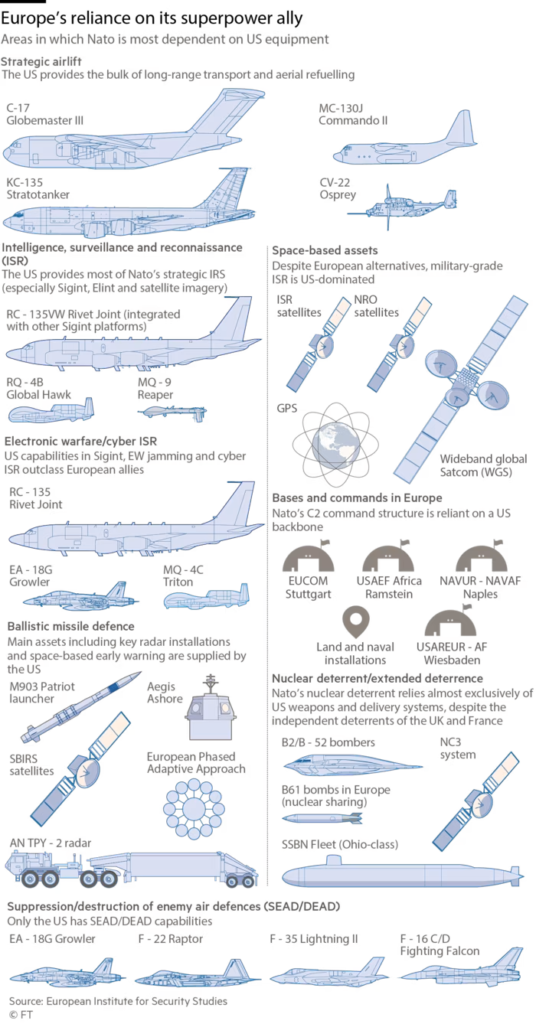

The alliance is heavily dependent on the US for crucial capabilities, in particular: intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance; combat communications and cloud computing; air defences; heavy transport aircraft; and suppression of enemy air defences. European Nato members also lack long-range precision strike missiles in sufficient quantity.

They would also have to do without a US force of 128,000 people that analysts say US commanders would typically deploy to a Nato operation against Russian attack.

Directly replacing the US contribution would cost $1tn, assuming one-off procurement costs and 25-year life cycle for equipment, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated in a report last year. In some cases, such as for spy satellites, filling the gap left by the US could take a decade or more.

On top of that, replacing the US nuclear deterrent in Europe, either by expanding the size and scope of British and French nuclear capabilities or developing a new platform, is a separate and additional challenge of an altogether different magnitude.

For Carlo Masala, professor of international politics at the Bundeswehr University Munich, fully substituting for the US is the wrong objective.

“It’s not about being as good as the US, which will take us 15 years or even longer. It is just being better than the Russians.”

That is “completely different” and achievable in three to four years, Masala adds.

Nato is also heavily dependent on the US for planning, command and control. Nato’s supreme allied commander, or SACEUR, is always a US officer, who is simultaneously in charge of US forces in Europe.

Nato’s command structure, defence plans and force commitments make it much more than a defence pact. It is, says Masala, an “interoperability machine” and there is no point in trying to replicate it.

European politicians often talk of a European pillar of Nato but seldom say what that entails. Nato officials and defence analysts say it would be better to envisage a Europeanisation of Nato for conventional defence — gradually supplanting US personnel and assets. It would also potentially align with the Trump administration’s burden-shifting agenda.

Matthew Whitaker, US ambassador to Nato, caused a stir in November when he said he “looked forward to the day” when a German officer could become SACEUR. An American SACEUR is in effect the link between conventional defence and the US nuclear deterrent, so to replace him with a European would in itself mark a drastic change.

But what if the US went rogue or obstructed the alliance? Commissioner Kubilius has floated the idea of a standing European army of 100,000 men instead of 27 modest national forces. But there is little appetite in European capitals to extend the EU’s powers in defence matters.

Macron, the leading voice for European strategic autonomy, told a gathering of French military personnel this month that European defence would rest on “the sovereign choices of each nation”.

Paris instead sees the “coalition of the willing”, the group of nations assembled under Franco-British leadership to aid Ukraine and prop up its postwar security, as a potential way of organising Europe’s defence.

Macron described the coalition this month as a “true revolution in joint strategy, capability and organisation”. It has the merit of including non-EU countries such as the UK, Norway and Turkey that are vital to Europe’s defence.

Nato powers could also increasingly operate through regional subgroups, such as the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force of northern countries or the Arctic nations. Even so, shifting collective defence to such a new and informal group seems a stretch.

Whether it is US disengagement or US hostility, the biggest challenge of all for European allies will be maintaining unity. There is already a growing tension between northern and eastern members spending heavily on their defence and more cash-strapped governments in the south and west.

Trump’s coercion over Greenland could have turned “toxic” for the EU as well, says Everts of the EUISS, because it would have tested the limits of internal solidarity. Its members may have closed ranks behind Denmark last week. “But if it really comes down to a choice, Greenland versus Ukraine or Greenland versus what is remaining of the Article 5 guarantee, are we going to maintain that level of unity?”

Stefano Stefanini, a former Italian ambassador to Nato, says US dominance of European security through Nato has provided one of the foundations of regional integration by taking divisive questions over military rivalry out of European hands.

“You take away that presence, and Europe disintegrates, as well as Nato.”

Nato members that are most wedded to America — Britain with its supposed “special relationship” or governments more ideologically aligned with Trump such as Italy — are the most reluctant to embrace the case for reform. If Nato crumbles or the US disengages, will they seek bilateral security guarantees or invest in collective European security?

European leaders are “torn because there is still hope we can manage the US, which means not spending even more on defence than we are doing already”, says Masala. “But intellectually speaking, they all realise that times have changed fundamentally. If you don’t want to be in between an aggressive regional power, Russia, and an aggressive global power, the US, you have to get into gear.”