The latest peace proposals are only a bit closer to what Ukraine and Europe need.

A christmas ceasefire in Ukraine? The German chancellor, Friedrich Merz, hopes for one. And the upbeat words of European and Ukrainian leaders, and American negotiators, after two days of talks in Berlin, made the prospect sound a little closer. They announced alignment on a package of nato-like security guarantees and economic support for Ukraine once the fighting stops. But many details are hazy and most need a lot more negotiation. Crucially, the proposals have yet to be put to Russia, which will no doubt object to many of them. Indeed, no one knows whether Vladimir Putin, Russia’s leader, is even interested in ending his onslaught, now nearly four years old.

For Ukraine, the dilemma remains unchanged. It cannot agree to surrender territory in a ceasefire deal without ironclad security guarantees. Yet the stronger the guarantees, the more likely Russia is to reject them. Ukraine and its European allies may be enthusiastic about the Trump administration’s shift in their direction, but when America shores up its gap with Europe, it widens its gap with Russia. And it is, anyway, hard to see the value of security guarantees from an America that has consistently stated and demonstrated that it will not go to war for Ukraine against Russia.

On the diplomatic plane at least, the talks in Berlin represent progress. For Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s embattled leader, closer consensus among its Western allies was a relief after weeks in which President Donald Trump appeared to blame Ukraine for the failure of diplomacy and blasted European allies as “decaying”. Now, Mr Zelensky said, “we’ve agreed on 90% of the issues.” Should Mr Putin reject the new terms, he added hopefully, he risks America’s president’s wrath: “I think America will press him with sanctions and give us more weapons.” For his part, Mr Trump sounded unusually optimistic. “I think we’re closer now than we have been ever.” Mr Zelensky and European leaders spoke of “strong convergence”. In early trading, oil fell below $60 a barrel for the first time since May, partly on hopes that more Russian oil would soon reach the market.

Achristmas ceasefire in Ukraine? The German chancellor, Friedrich Merz, hopes for one. And the upbeat words of European and Ukrainian leaders, and American negotiators, after two days of talks in Berlin, made the prospect sound a little closer. They announced alignment on a package of nato-like security guarantees and economic support for Ukraine once the fighting stops. But many details are hazy and most need a lot more negotiation. Crucially, the proposals have yet to be put to Russia, which will no doubt object to many of them. Indeed, no one knows whether Vladimir Putin, Russia’s leader, is even interested in ending his onslaught, now nearly four years old.

For Ukraine, the dilemma remains unchanged. It cannot agree to surrender territory in a ceasefire deal without ironclad security guarantees. Yet the stronger the guarantees, the more likely Russia is to reject them. Ukraine and its European allies may be enthusiastic about the Trump administration’s shift in their direction, but when America shores up its gap with Europe, it widens its gap with Russia. And it is, anyway, hard to see the value of security guarantees from an America that has consistently stated and demonstrated that it will not go to war for Ukraine against Russia.

Read more of our recent coverage of the Ukraine war

On the diplomatic plane at least, the talks in Berlin represent progress. For Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s embattled leader, closer consensus among its Western allies was a relief after weeks in which President Donald Trump appeared to blame Ukraine for the failure of diplomacy and blasted European allies as “decaying”. Now, Mr Zelensky said, “we’ve agreed on 90% of the issues.” Should Mr Putin reject the new terms, he added hopefully, he risks America’s president’s wrath: “I think America will press him with sanctions and give us more weapons.” For his part, Mr Trump sounded unusually optimistic. “I think we’re closer now than we have been ever.” Mr Zelensky and European leaders spoke of “strong convergence”. In early trading, oil fell below $60 a barrel for the first time since May, partly on hopes that more Russian oil would soon reach the market.

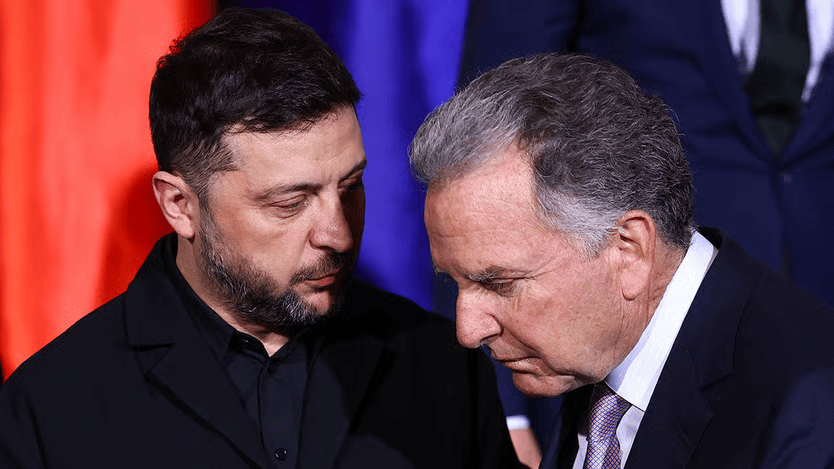

The agreement on the outlines of security guarantees for Ukraine was negotiated between the Europeans and two American envoys, Steve Witkoff (pictured, with Mr Zelensky) and Jared Kushner, the president’s golfing buddy and son-in-law respectively. American officials described the guarantees as “platinum-standard”, though the details are scarce. Ukraine will not be admitted to nato, but America and European countries would offer a pledge that mirrors nato’s Article 5, which holds that an armed attack on one ally is an attack on all. To lend credence, Mr Trump apparently stands ready to submit the guarantee to the Senate, although the officials did not specify whether this would be a treaty or a less binding resolution.

In case of a future attack by Russia, European leaders said, the Western response “may include armed force, intelligence and logistical assistance, economic and diplomatic actions”. Such measures fall well short of treating Ukraine as a fully fledged ally. Whereas nato countries engage in joint deployment, exercises and planning, American officials said there would be no American boots on the ground. The question is what degree of support they are actually willing to offer. The Americans said there would be extensive provisions to monitor the ceasefire and “deconflict” the rival forces to avoid clashes. European officials claimed—or maybe just hope—the mission would be led by America.

Ukraine thus gets what looks at most like a second-best assurance. Under the outline, it would be able to keep its armed forces at their current strength of 800,000. They would be supported by a European “coalition of the willing”, backed in a still-undefined way by America. The aim would be to “assist in the regeneration of Ukraine’s forces, in securing Ukraine’s skies, and in supporting safer seas, including through operating inside Ukraine”. Further details are due to be discussed by military officials in the coming days, possibly in Miami.

On the economic side, there would be a support package to ensure a “bright and prosperous future” for Ukraine, as well as the prospect of eu membership, the American officials say. The financial plan is being drawn up by the World Bank and a pro bono team from BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, with extensive financing from European countries.

How far it may use frozen Russian assets is unclear. The eu has indefinitely immobilised €210bn ($247bn) worth of assets. Its leaders will meet on Thursday to discuss using the funds for a “reparations loan”, worth perhaps €90bn by the end of 2027, to fund Ukraine. Kaja Kallas, the eu’s foreign policy head, said agreement was “increasingly difficult” given objections from Belgium, where most of the funds are held, and a growing band of dissenting members, spurred in part by American objections.

Ukraine is pressing Europe to use the Russian assets. “Russians don’t count their own dead, but they do count every dollar and every euro they lose,” Mr Zelensky told the Dutch parliament on December 16th. He was in The Hague for the launch of another possible source of funding: an international commission where claims can be lodged against Russia for damage in Ukraine. But America is much less eager to make Russia pay. An early version of the American peace plan included provisions to use part of the Russian assets for bilateral US-Russian economic projects. And the American officials said the latest iteration seeks to ensure that “Russia gets back into the global economy”.

The trickiest question concerns Russia’s demand that Ukraine surrender all of the Donbas region, including parts it still holds. American officials have suggested turning these lands into a “free economic zone.” Mr Zelensky insisted that Ukraine would not surrender sovereignty over them, and that any Ukrainian withdrawal from fortified parts of the Donbas must be matched by a Russian military pull-back.

Messrs Witkoff and Kushner seem convinced that business deals will ensure a future peace holds, and that Russia will agree to the security guarantees in a final deal. “There’s no such thing as permanent allies or permanent enemies,” insists one American official. Such language, intended to encourage hopes of peace, may instead deepen suspicions: is Mr Trump now less committed to European allies, and intent on embracing Russia? His officials, after all, say the guarantees “will not be on the table for ever”.

On reflection, the leaders’ pronouncements in Berlin seem far too rosy. The security guarantees for Ukraine depend on unspecified deployments by European countries with few troops to spare, possibly led by an America whose willingness to defend Ukraine in case of renewed attacks is questionable. Pledges that mimic nato’s Article 5 mean less in a world where America’s commitment to nato itself is ambivalent. The source of the mooted financing for rebuilding Ukraine is unclear. On territory, the biggest achievement is that America’s envoys, who recently floated proposals that would in effect recognise Russian sovereignty over occupied land, seem willing to accept a proposal that does not.

Nonetheless, the ball is now back in Russia’s court. Some think Mr Putin might pocket territorial concessions, if he thinks it will split Ukraine and divide America from the rest of nato. Others think that is beyond him. “There is no way he accepts security assurances or [the presence of] nato forces in Ukraine,” says Ivo Daalder, a former American ambassador to nato. “This is all about trying to please Trump, not to get to a real deal.”

In the first world war, the Christmas truce between German and allied soldiers in the winter of 1914 was short-lived. In Ukraine, it may be non-existent.