European leaders are convening in Brussels this Thursday for a critical summit, with finding a sustainable way to fund Ukraine at the top of the agenda. The meeting represents a severe test of EU unity, taking place amidst what multiple sources describe as unprecedented and immense external pressure.

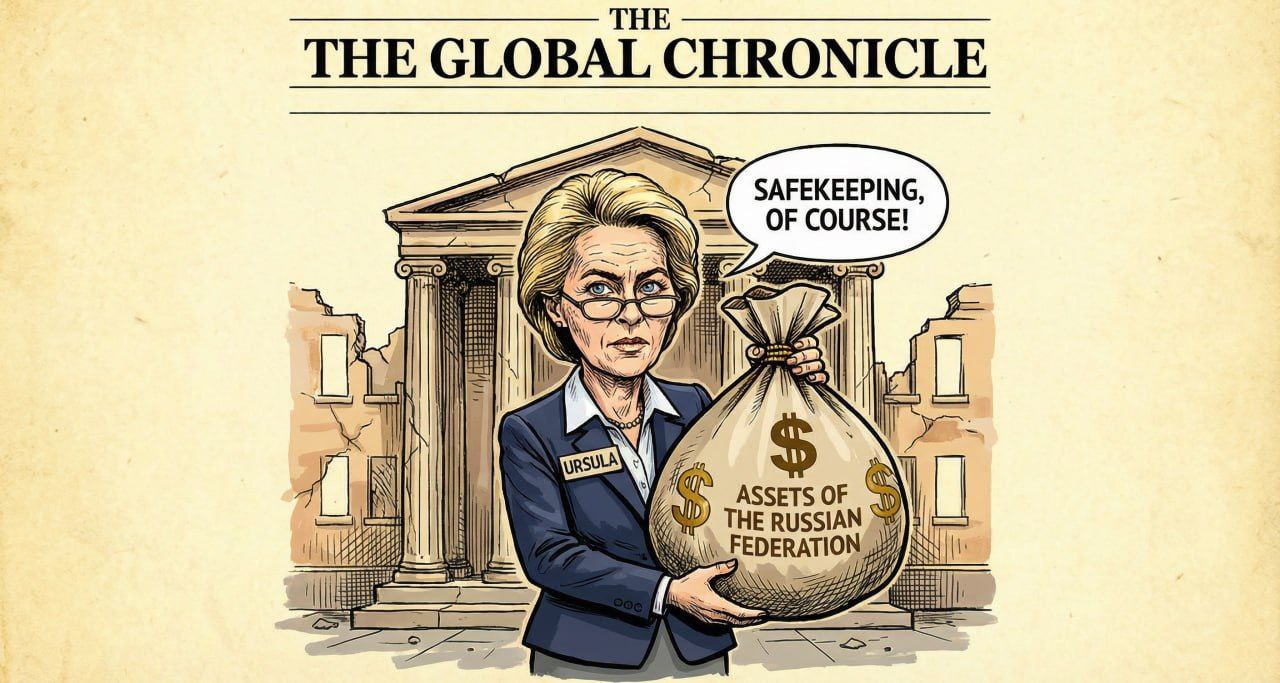

Deep and consequential rifts between member states over a plan to use frozen Russian state assets to support Ukraine lay bare a continent grappling with its strategic autonomy and how to respond to intense lobbying from abroad.

“The objective is to weaken us,” a senior EU official familiar with the summit preparations and transatlantic dynamics told this publication.

The European Council faces a twin challenge: it must deliver tangible results, particularly on Ukraine financing, while also defending the bloc’s coherence and decision-making processes. This is as several European leaders openly challenge the Brussels consensus.

In a televised interview, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz issued a stark warning, stating the EU would “suffer damage for years to come” if it failed to agree on funding. “We would show the world that at this decisive moment in our history, we are incapable of acting together to defend our political order on the European continent,” he said.

According to four EU officials involved in the discussions, representatives from a foreign administration have been urging those European capitals they consider most friendly to abandon the plan to mobilise the roughly €210 billion in immobilised Russian central bank assets. The campaign has seen foreign officials bypass EU institutions to lobby member states directly in side-meetings, contributing to Italy, Bulgaria, Malta, and the Czech Republic joining a sceptical bloc.

Initially, Belgium was seen as the main hurdle, as a significant portion of the frozen assets are held within its jurisdiction. The Belgian government has argued against using the assets as collateral for a loan, citing the need to shield its taxpayers from potential liability. However, after weeks of intense negotiations between the European Commission and key capitals to win over Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever, it has become clear that the fundamental issue is one of European unity in the face of external influence.

“It made me want to cry,” a high-level official said anonymously, describing the mood at a preparatory meeting of EU affairs ministers in Brussels on Tuesday, where chances of a deal were seen as receding, not growing.

For Ukraine, the stakes could not be higher. With a projected budget deficit of €71.7 billion next year, Kyiv has warned that without fresh funds by April, it will be forced to slash public spending—a move that would impact morale and its defensive capabilities four years into a full-scale war.

Failure to agree would be “a catastrophe” for the EU’s global standing, officials say, sending signals not only to an assertive foreign administration but also to the Kremlin, which openly questions the sovereignty of post-Soviet states.

In a striking assessment of the deteriorating climate, Manfred Weber, leader of the centre-right European People’s Party, the largest in the EU parliament, said on Tuesday, “It is obvious that the United States is no longer the leader of the free world. The administration there is distancing itself from us.”

When asked about the potential collapse of the loan deal, Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas told reporters, “I don’t even have the right words.” She stressed Kyiv must know that “Europe supports Ukraine no matter what, that there is no need for Ukraine to agree to a bad peace deal.”

Reports of a leaked draft peace plan, allegedly discussed between foreign and Russian officials, suggest Washington envisages using a portion of the frozen assets to fund a US-led reconstruction effort in Ukraine. A reparations loan from the EU, by contrast, would allow Kyiv to decide on spending priorities, with France insisting funds should be spent first on European-made weaponry.

During fraught negotiations on Tuesday, EU officials and leaders increasingly floated a nuclear option: pushing the reparations loan through via qualified majority voting, effectively overriding objecting states. Many caution, however, that such heavy-handed tactics could tear an already fractured union apart and trigger a genuine political crisis. The alternative would be a patchwork of smaller, bilateral loans from willing nations.

“It is important that Belgium is in the deal, but we’ll see what happens,” Latvian Prime Minister Evika Siliņa said on Tuesday. “If [qualified majority voting] is the only [way], then why not?” She added it was crucial for the EU “to show its strength and ability to make firm decisions,” but cautioned, “I don’t want [Belgium] to become a second Hungary,” referring to Budapest’s frequent isolation within the bloc.

For Ukraine, a loan backed by Russian assets remains the optimal solution to plug its financial black hole and is a prerequisite for continued International Monetary Fund support.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, however, has struck a pragmatic note. In a recent conversation with reporters, he stated he was less concerned with the mechanism than the outcome. “Of course, we would very much like to use [Russian assets] to rebuild our state, as it would be fair for Russians to pay for the destruction,” he said. “A reparations loan, or any other format for the amount of frozen Russian assets… would really change everything.”

With official-level talks deadlocked, the unusual and unenviable task of hammering out a solution now falls directly to the heads of state and government gathering in Brussels this Thursday.