An increase in hate crime comes as aid for Kyiv takes center stage in a political battle in Warsaw.

When the man heard Oleksandra Iwaniuk speaking Ukrainian with a friend on a crowded tram in Warsaw, he launched into a tirade of verbal abuse. Bald and wearing military camouflage, he addressed his slurs in Polish to the whole carriage, never making eye contact with the two women.

“Everybody could hear him, but the most striking thing to me was that nobody reacted,” recalled Iwaniuk, 39, an academic who has lived in the Polish capital for 15 years, long before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “I realized that I didn’t have courage to address him myself because it really felt like there could be physical violence.”

With anger at immigration being stoked up across Europe, it’s the kind of attack that could have happened in many places. But the incident exposes the shift in a country whose economy has boomed with the help of Ukrainian labor and is the main conduit for Western aid to the Kyiv government’s war effort.

The scene might have been unimaginable in the months after Vladimir Putin sent in troops in February 2022, when millions of Ukrainians fled for the safety of a largely welcoming neighbor. The cracks in that solidarity are now becoming more evident, with opposition to supporting Ukraine taking center stage in a power struggle at the top of Poland’s politics.

A month after the full-scale invasion, a survey by Warsaw-based pollster CBOS found that 94% of Poles wanted to accept Ukrainian refugees. A CBOS survey last month put that support at 48%, with half of Poles now believing that state benefits offered to Ukrainian arrivals are too generous.

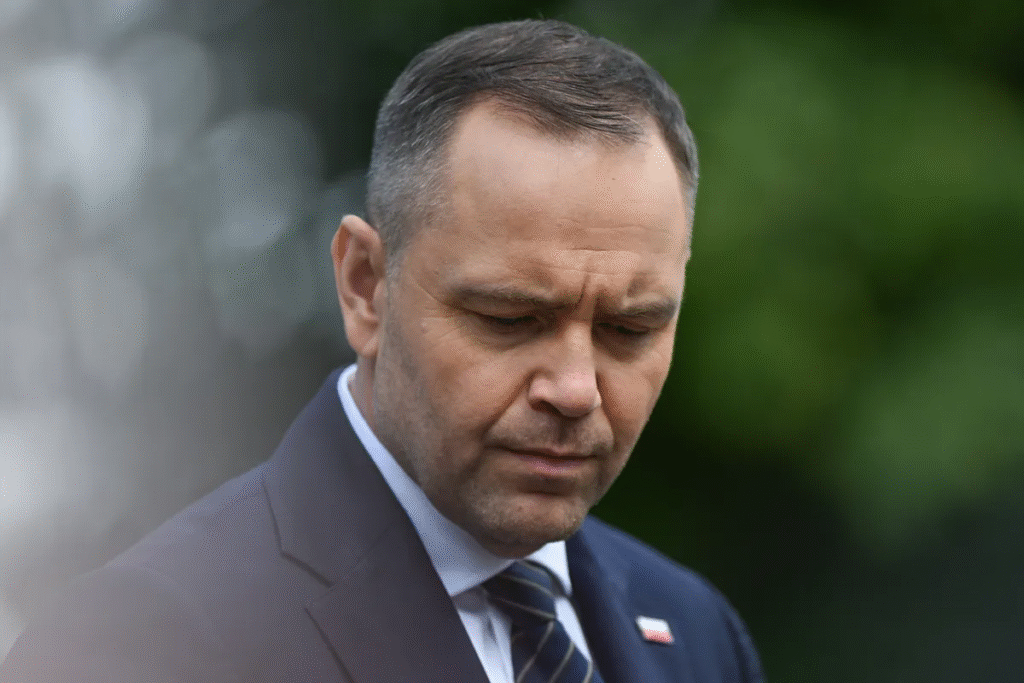

President Karol Nawrocki, who scored a shock election victory earlier this year by beating Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s candidate for head of state, has voiced skepticism of Ukraine’s aspirations for NATO and European Union membership. He and allies in the opposition Law & Justice party have accused refugees of jumping the queue for social welfare. Nawrocki vetoed a bill in August extending support to them.

Meanwhile, Tusk’s government is focusing on the realpolitik of defending Poland, spending more money on defense than any other NATO member relative to the size of the country’s economy.

“It’s a big question how Nawrocki will reconcile the interests of Polish national security with the increasingly anti-Ukrainian mood among the right-wing electorate,” said Piotr Buras, senior policy fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Warsaw.

Poland sent billions of zloty in military and financial aid to Kyiv following Russia’s attack. For strategic and money reasons, the shipments of arms have been replaced by political support and the logistical use of its territory.

Warsaw has been a welcoming place for Ukrainians in the main. Migration to Poland gathered pace in 2015 as Ukraine was gripped by an economic crisis, with more incomers taking temporary jobs in factories, construction or the service sector. Putin’s invasion then triggered a new wave and about a million Ukrainians are still under temporary protection in Poland, according to the European Commission.

Brands familiar to any Ukrainian have set up shop. A branch of The Drunken Cherry serves up Ukrainian liquors in the shadow of the Palace of Culture, Warsaw’s iconic Stalin-era skyscraper. A Lviv Croissants bakery is just a stroll away.

Economists stress the contribution Ukrainian immigrants have made. The Polish Development Bank in March estimated that Ukrainian workers, including those who immigrated before 2022, contribute as much as 2.4% of Polish gross domestic product, which recently topped $1 trillion.

A report for 2024 found that 78% of displaced Ukrainians in Poland were employed, more than any other member of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

“Thanks to Ukrainian migrants, we could fill labor shortages amid a huge demographic decline,” said Jan Brzozowski, an economist at the Institute for European Studies at the Jagiellonian University of Krakow. He warned the country shouldn’t take Ukrainians for granted.

“They’re not necessarily forced to stay in Poland, so could move to Germany, France or other EU countries,” he added. “The negative attitude toward them will play a part.”

Statistics on hate crime and discrimination are complicated because many victims don’t report incidents and when they do, nationality or ethnicity isn’t always stated. Police said they recorded 651 cases against Ukrainian citizens in Poland in 2024 and 477 in the first nine months of this year.

The commissioner for human rights, meanwhile, observed a “growing number of acts of discrimination and hate speech directed towards the Ukrainian citizens residing in Poland,” according to a statement from the country’s ombudsman. In the case of Iwaniuk and her friend on the tram during the summer, their verbal attacker used an abusive term for eastern Slavs.

The Never Again Association, an NGO based in Warsaw that compiles data on racism and xenophobia, said the number of physical attacks on Ukrainians also increased between 2024 and 2025.

The figure of the “ungrateful Ukrainian” looms large in anti-Ukrainian narratives, said Olena Babakova, a migration researcher and analyst. When Poles met Ukrainians who wouldn’t take just any job and could compete with them, it violated an unspoken social contract, she said.

Babakova, a Ukrainian who has lived in Poland for 17 years, has witnessed the resentment first hand. She recalls an incident at a Warsaw playground that speaks to the fact that for some Poles, Ukrainians can never fully belong.

“My child was playing in the sandbox at the playground with a little girl and when her father heard my Ukrainian accent he took her back and commented loudly why he took her back, saying ‘you won’t play with that Ukrainian boy’,” said Babakova. “My child is a Polish citizen. He speaks Polish.”

Indeed, times are tense in Poland, which recently suffered a wave of drone incursions from Russia and also is seeing a renewed influx of Ukrainians.

Poland’s Border Guard Service registered more than 98,500 entries by young Ukrainian men aged 18 to 22 in two months through Oct. 26. The increase comes after President Volodymyr Zelenskiy eased departure rules. Less than half that number entered Ukraine.

Ukrainian and Polish politicians blame Moscow for the increase in hostility. According to a study by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in May, pro-Russian actors fueled anti-Ukrainian sentiment during Poland’s presidential election, including by falsely accusing refugees of preparing terrorist attacks.

There’s also the usual historical tropes. Russia’s war led Kyiv and Warsaw to temporarily set aside disputes such as the Volhynia massacres, in which Ukrainian nationalists targeted ethnic Poles during World War II. Both sides agreed this year to allow exhumations.

But the tragedy, which Poland regards as genocide, has regained prominence, with politicians warning at a memorial event in July that it’s fertile ground for Russian attempts to undermine unity between Poland and Ukraine.

At a rap concert at Warsaw’s National Stadium in August, clashes broke out between fans and security staff with footage of one concertgoer displaying a flag associated with World War II era Ukrainian nationalists. On the back of public outrage at that symbol, Prime Minister Tusk declared the expulsion of 63 people, including 57 Ukrainians.

When a group of young Ukrainian men were set upon by a group of Poles in the Warsaw suburb of Bialoleka in September, their attackers told them to get back to the front, accusing them of being nationalists, according to local media reports.

Polish appetite to help comes in peaks and troughs — possibly with more troughs, Buras said. The initial wave of support after 2022 is now “exhausted,” he said, noting that Polish enthusiasm for Ukraine after the 2014 Maidan Revolution suffered the same fate.

For Iwaniuk, the incident on the tram during the summer has reversed years of progress. The response to Putin’s invasion had made her feel like speaking Ukrainian in public suddenly wasn’t anything to be shy about in Poland.

“I finally felt that I didn’t have to worry anymore about how I’d be perceived in public,” she said. “I don’t want to say the wave of solidarity stopped because many people still do a lot of things for Ukrainian refugees, but the atmosphere has been very clearly changing towards hostility and aggression.”